Manet / Degas at

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Self-Portrait, Édouard Manet (1878-1879)

Private Collection

I wasn’t originally planning on visiting Manet / Degas. I’m in the middle of planning a trip to several art museums in Europe (to my regular readers, details coming soon!), so adding a weekend in New York City seemed exhausting. Yet one of the highlights of this upcoming European adventure was supposed to be Manet’s Olympia, which is currently, as you can probably guess, in New York. So I met up with my friends that live near the city and went to the Met, and proceeded to be sucked into Manet and Degas’s world of 19th Century Impressionists.

I loved this exhibition. We went on a Saturday night, so we got to enjoy live music and all that the Met has to offer while we waited in the virtual queue for access to Manet / Degas. Inside the exhibition, we were all captivated by the dialogue between the two artists, and I got to cross seeing Olympia off of my bucket list.

Read on to see my highlights from the exhibition and discover the complex personal and professional relationship between Manet and Degas.

Self-Portrait, Edgar Degas (1855)

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

In the Beginning

The Infanta Margarita, after Velázquez, Édouard Manet (1861-1862). Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

Manet and Degas knew each other well. They often inspired each other’s works and created their own interpretations of the same subjects. But how did they meet?

The story goes that they met at the Louvre in Paris in front of Portrait of the Infanta Margarita Teresa by Diego Velázquez. Degas was etching the drawing, and Manet commented on how untraditional it was to etch in the museum instead of making a sketch and etching in a studio.

Manet would later go on to also making an etching of the painting. However, the two artists would take different approaches. Degas etched the painting as he saw it, so the resulting image is backwards. Manet’s etch is backwards, so his print is oriented the same way as the original painting.

This theme of Manet’s tradtional approach to things versus Degas’s interest in the untraditional will continue throughout their careers.

The Infanta Margarita, after Velázquez,, Edgar Degas (1861-1862). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Painting the Manets

Madame Manet at the Piano, Édouard Manet (1867-1868). Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Manet was also a more traditional family man than Degas. Degas maintained his reputation as a bachelor, but was interested in Manet’s lifestyle. He painted Monsieur and Madame Manet while Madame Manet played the piano. Upon gifting the painting to Manet, Manet cut the canvas. He was reportedly obsessed with drawing his wife’s profile perfectly, and likely felt that Degas did not paint her correctly. He was apparently much happier with his own Madame Manet at the Piano.

Despite appearing very traditional, the Manets were not without their secrets. Madame Manet, Suzanne Leenhoff, had a son out of wedlock that Manet raised as his own. The boy might have been Manet’s biological son, but also could have been the result of an affair Suzanne was having with Manet’s father.

Monsieur and Madame Manet, Édgar Degas (1868-1869). Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The Paris Salon

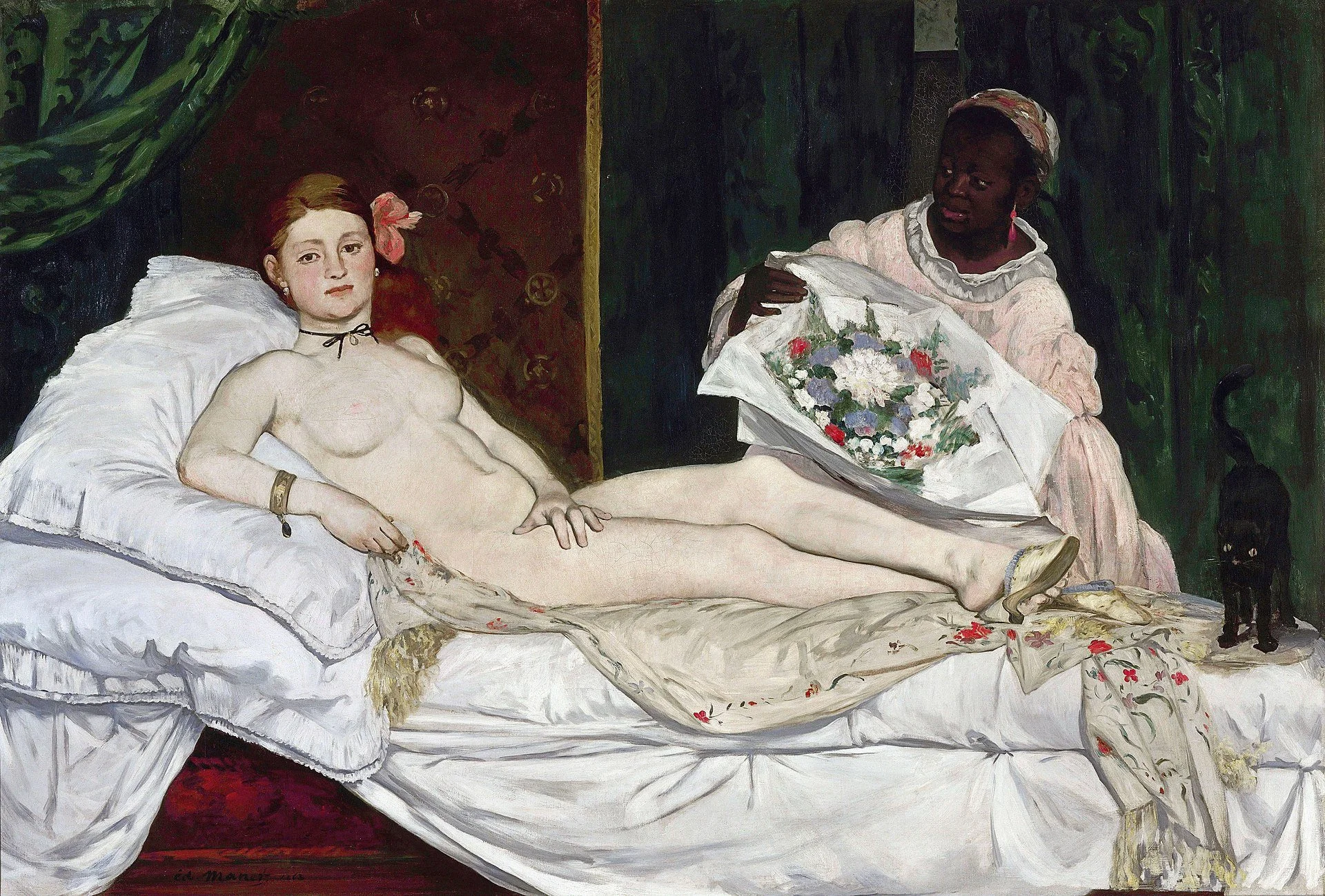

Olympia, Édouard Manet (1865). Musée d’Orsay, Paris

In the 1800’s, the Salon of Paris was quite possibly the most important event for artists in the world. It was a prestigious institution that determined the trends and standards of the art world, and many of artists submitted pieces annually with the hope of their work being chosen. It was a high honor to display work at the Salon, and attention from critics was important for a growing artist’s career.

In 1865, both Manet and Degas exhibited pieces at the Salon. However, the reception of their works could not have been more different.

Degas’s work, Scene of War in the Middle Ages, was unremarkable. It was the product of a significant amount of preparation and hard work, yet critics largely ignored the piece. Scene of War in the Middle Ages didn’t have a bad reception. It simply got no attention, which was, in a way, worse. This eventually caused Degas to abandon both history painting and the Salon entirely.

Manet’s Olympia, however, made quite a splash. It was a reinterpretation of a Renaissance Masterpiece (Titian’s Venus of Urbino) that overtly depicted a prostitute. Controversy came from the subject matter, but also from the fact that Manet painted a nude woman without the guise of mythology. Viewers had to confront the nudity of a real, contemporary Parisian woman, and Olympia confronts them right back.

Everything about her, from her name to the orchid tucked behind her ear to the black cat at the foot of her bed, tells us that she is a prostitute. Yet her direct gaze and the rigid, almost protective, position of her hand is anything but sensual. She even ignores the bouquet of flowers from a client that her maid presents. She is not a one-dimensional, hyper-sexualized courtesan. Instead, she is a woman who seems highly disinterested in her line of work.

Scene of War in the Middle Ages, Édgar Degas (1865). Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Growing Careers

The Balcony, Édouard Manet (1868-1869). Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Despite the vastly different reception at the Salon, both Manet and Degas continued to work and develop their own styles. While both artists are considered ‘Impressionists’, their styles varied greatly. The Balcony and The Orchestra of the Opera are some of the best examples of their respective artists’ interests and talents.

Manet’s The Balcony again drew controversy. Critics claimed that Manet’s colors were too bright, and that he spent his time painting the ‘wrong’ things. The flowers in the foreground are more detailed than the portrait of his son, half hidden in shadow. The painting is a bit strange, but it is captivating all the same. It demonstrates Manet’s interest in portraits and urban scenes.

During this period, Degas began to paint two of his favorite subjects- horse races and ballet dancers. Degas was also interested in finding unique perspectives from which to paint. In The Orchestra of the Opera, Degas barely paints the dancers. Instead he shows us the often-overlooked orchestra pit. He captures the motion and liveliness of the scene with his friend, the bassoonist Désiré Dihau, at the center.

The Orchestra of the Opera, Édgar Degas (1870). Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Café Scenes

Plum Brandy, Édouard Manet (1877).

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

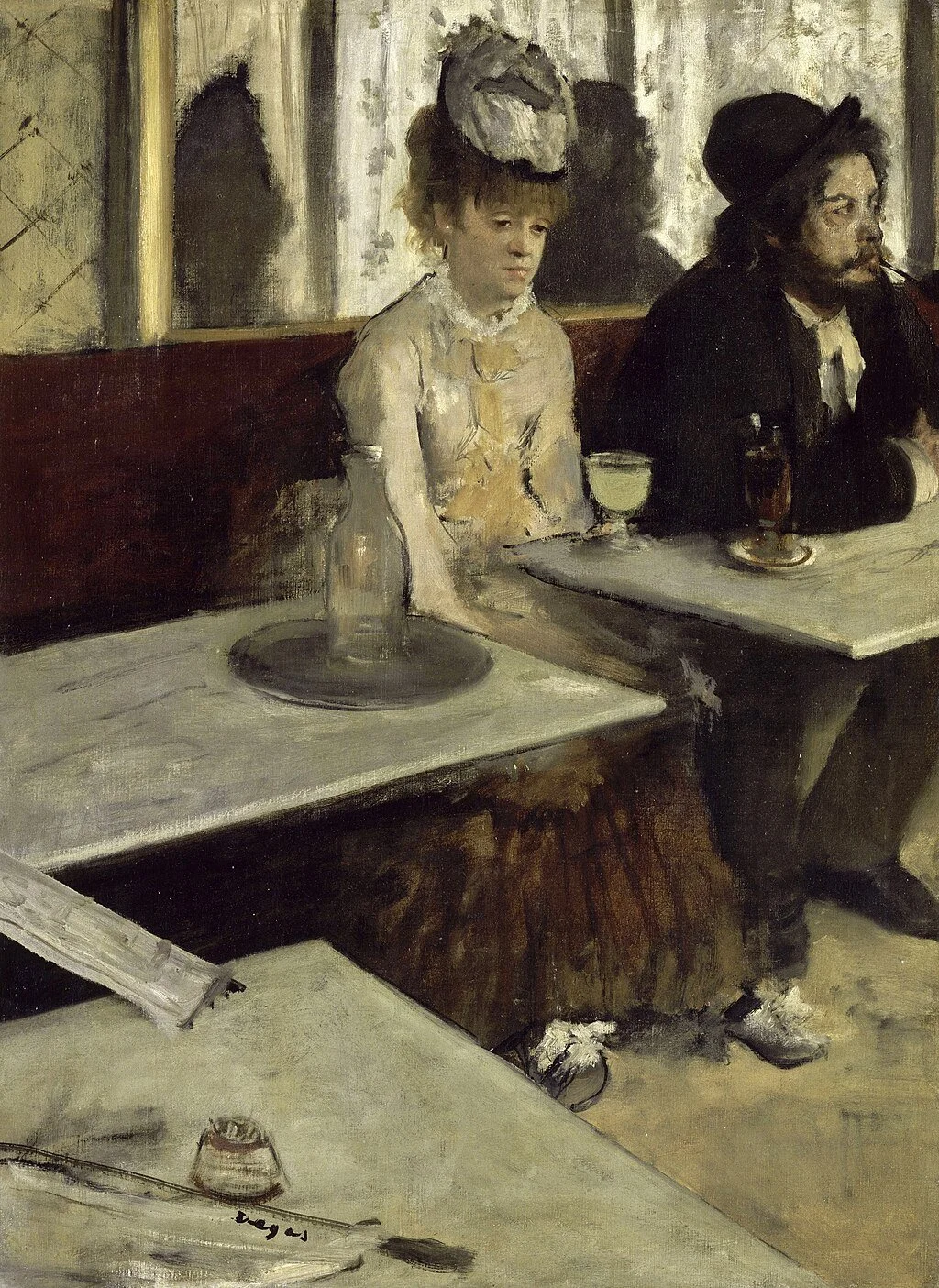

Contemporary life in Paris was a popular subject matter for the Impressionist artists. Both Manet and Degas wanted to capture the feeling of an urban café, and produced two very similar paintings.

Both Plum Brandy and The Absinthe Drinker depict model Ellen Andrée seated against the back wall of a café with a drink. She seems to be contemplating something, ignoring her drink in favor of staring into space lost in her own thoughts. They evoke a feeling of loneliness, likely as commentary on how isolated one can feel even in a place as populated as Paris.

Degas also does something very interesting with his composition. Manet gives us a more traditional portrait, with the subject at the center and taking up most of the canvas. Degas, however, places his subject in the upper right corner. This is because we, as the viewer, are part of the scene. We’re seated at out own table in the bottom left, looking at the woman a few tables over.

The Absinthe Drinker, Édgar Degas

(1875-1876). Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Mourning Manet

The Execution of Maximillian, Édouard Manet (1867-1868)

The National Gallery, London

In 1883, Édouard Manet died. Degas mourned his friend, and began collecting as many of Manet’s works as he could.

One of the most ambitious tasks Degas undertook was the reconstruction of Manet’s Execution of Maximillian. The work received little attention while Manet was alive, as the subject was too political and controversial to display publicly.

It is unclear exactly when or why the piece was fragmented, but it is believed that some of the pieces may have been sold to collectors after the artist’s death. However, Degas sought to repair the piece, buying and reassembling as many of the pieces as he could.

The work is displayed alongside several others by Manet that Degas kept in his personal collection. The collection as a whole allows us to truly appreciate how much Degas valued Manet as an artist and friend.

Manet / Degas will be on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through 1/7/2024. I highly recommend joining the virtual queue as soon as you arrive in the museum to ensure that you’ll be able to enter the exhibition.