The Tudors

Exploring The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England at the Cleveland Museum of Art

Who Were the Tudors?

Allegory of the Tudor Dynasty, William Rogers, after Lucas de Heere (ca. 1595–1600) The British Museum, London

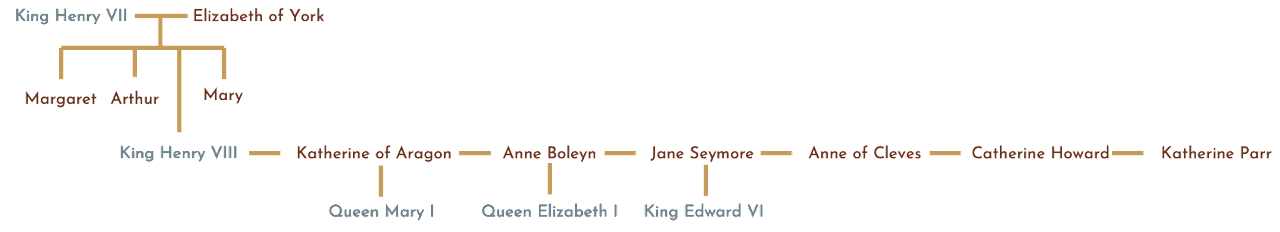

The Tudors were the monarchs of England from 1485 to 1603. King Henry VII was the first of the Tudor rulers, coming to power after defeating Richard III and ending the War of Roses.

Henry VIII is one of England's best known monarchs, famous for his break from the Catholic Church that began the English Reformation, and for his six wives. After Henry VIII's death in 1547, his son, Edward VI, became king at only 9 years old. Edward VI died young and left the throne to his older half-sister, Mary I, also known as 'Bloody Mary', who became the first queen of England in 1553. Finally, Elizabeth I, the 'Virgin Queen', took the throne in 1558 and died childless in 1603, ending the Tudor line.

The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England is a collection of art and artifacts from this period, giving us a glimpse into the lives of these monarchs and their contemporaries. Read on to discover the story of religious upheaval, love affairs, book burnings, and beheadings through the art of Tudor England, and visit the exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art through 5/14/2023.

Henry VII - Designing a Dynasty

Henry VII Cope, Florence or Lucca (1499–1505) Trustees of the British Jesuit Province-Jesuits in Britain

King Henry VII's Cope serves as a visual representation of the creation of the Tudor dynasty. He came to the throne after the War of Roses, a civil war between the Lancasters and the Yorks. Henry was a descendant of the Lancasters, and his defeat of King Richard III and marriage to Elizabeth of York put an end to the war through both military victory and political union.

Within his cope, we see three of the house symbols- red roses for Lancaster, grated gates, known as portcullis, for Beaufort (Henry's mother's house, who descended from the Lancasters), and the red and white Tudor roses, which combined the Lancaster roses with white York roses to create a new symbol of unity.

This cope was part of a larger set that was produced in Italy and was estimated to have cost around the Tudor era equivalent of £100,000.

Creation and Fall of Man, Unknown Flemish Artist (c. 1497) Cathédrale Saint-Just-et-Saint-Pasteur, Narbonne

With the purchase of Creation and Fall of Man, along with the other nine (now missing) tapestries in the set, King Henry VII solidifies his role as an important patron of the Renaissance.

Despite the fact that weavers could only finish about 5 square feet a month and the entire set spanned over 1/5 of a mile, it is estimated that all ten tapestries were delivered to the King in about 18 months. Weavers worked on all of the tapestries simultaneously to complete the order quickly.

This tapestry tells the story of Adam and Eve (the nude figures shown three times on the right). The other three figures, repeated seven times, are the trinity- Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. They appear seven times to represent the seven days of Creation.

Henry VIII - Renaissance, Reformation, and Six Wives

Henry VIII, Workshop of Hans Holbein the Younger, (c. 1540) Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool

Henry VIII's full length portrait is an impressive display of the King's wealth. He is draped in jewels, furs, and expensive fabric, and stands on an imported Turkish carpet. His pose and possessions make him appear powerful.

Portraits of the king were a popular subject. This painting was likely the product of the workshop of Hans Holbein the Younger, meaning that courtiers didn't care as much about commissioning a piece from a major artist as they did about owning an image of their king.

In addition to wanting to display his wealth, King Henry VIII wanted to celebrate his physical strength. He valued the military and likely commissioned this gilded and richly decorated armor. He had an entire team of armorers working for him, producing elaborate and expensive pieces for both personal use and to give as gifts.

Field Armor, Probably Made for King Henry VIII (1527) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

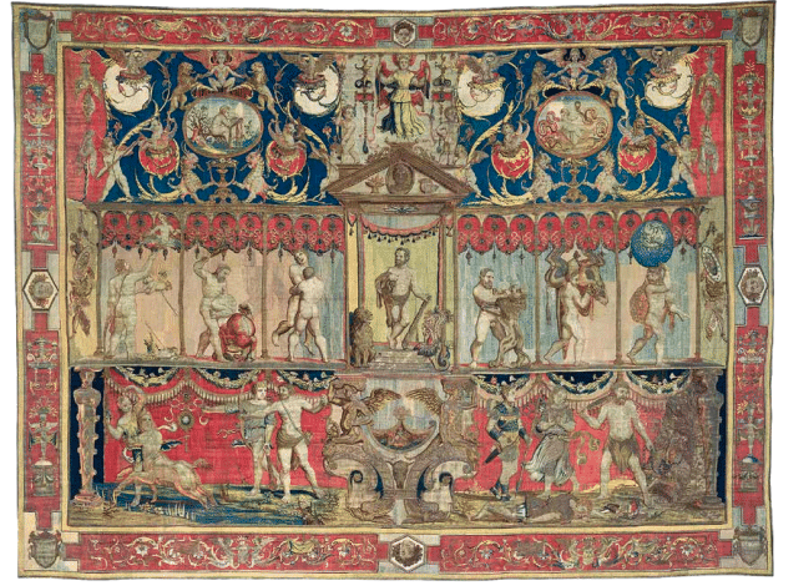

The Triumph of Hercules, from a Seven-Piece Set of the Antiques,

Designed by Raphael, with Giovanni da Udine, Perino del Vaga, and Gianfrancesco Penni (ca. 1516–20). Probably woven under the direction of Jan and Willem Dermoyen (before 1542).

The Royal Collection / HM Queen Elizabeth II.

Like his father, King Henry VIII wanted to be seen as a patron of the Renaissance, a feat he accomplishes with the purchase of The Triumph of Hercules, along with the other six tapestries in the set.

The set was designed by the Italian Renaissance Master Raphael and his workshop. Henry's set was likely a copy of tapestries made for Pope Leo X.

The design is inspired by Ancient Roman art, which was increasingly popular during the Italian Renaissance. Raphael's three-tiered design and grotesque figures were unprecedented. Even though the tapestry has dulled with time, we can still appreciate the bold colors and detailed figures.

In addition to the Antiquities set, Henry also purchased the (now lost) Acts of the Apostles set, which was also designed for Pope Leo X by Raphael.

Saint Paul Directing the Burning of the Heathen Books, from a Nine-Piece Set of the Life of Saint Paul

Designed by Pieter Coecke van Aelst (ca. 1535); possibly woven under the direction of Paulus van Oppenem (before 1539). Private collection

King Henry VIII's acquisition of Saint Paul Directing the Burning of Heathen Books was motivated by more than just his desire to collect tapestries. The tapestry design was popular amongst other monarches, with royalty in France, the Netherlands, and Hungary owning their own versions of the work.

For Henry in particular, the work legitimized some of the policies introduced under his reign. Before splitting from the Catholic Church, Henry ordered the burning of many books that were deemed 'heretical', including an English translation of the bible.

One of the most impressive features of the tapestry is how well some of the golden thread is preserved. It is easy to imagine when viewing this work how impressive all of Henry VIII's tapestries would have looked in their glory, sparkling in the candle light.

Nonsuch Palace from the South, Joris Hoefnagel (1568), Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In addition to purchasing tapestries, King Henry VIII also commissioned a palace. Nonsuch, named for the belief that no other building could compare to it, was inspired by Italian Renaissance architecture and designed to celebrate the Tudor dynasty. Construction started to commemorate the birth of King Edward VI and King Henry VIII's 30th year on the throne.

Despite the fact that Henry spent the equivalent of $13 million on the palace, it was not completed until after his death. It was then passed around by royals and courtiers, until it was disassembled and sold for the materials in the late 1600s.

Hoefnagel's drawing shows us the south side of the palace, giving us an idea of what it looked like in its prime. It also serves as one of the oldest examples of English landscape painting.

Anne Boleyn, Hans Holbein the Younger, (1533-36). The Royal Collection / HM Queen Elizabeth II

Anne Boleyn is arguably the most famous of Henry VIII's six wives. She was his second wife, and Henry's desire to marry her was, in part, what began England's split from the Catholic Church.

Henry's first wife, Katherine of Aragon, had originally been wed to Henry's brother, Arthur, before his untimely death. Katherine then married Henry, but failed to give him a son. Henry wanted to leave Katherine and marry Anne, and requested an annulment of his marriage from the Pope on the grounds that Katherine had been married previously. The Pope denied his request, prompting Henry to leave the Catholic Church in favor of Protestantism, which allowed him to divorce Katherine and marry Anne.

Anne would go on to give birth to future Queen Elizabeth I, but again failed to give Henry a son. He began courting Jane Seymour, and accused Anne of adultery and sentenced her to death. Anne Boleyn was beheaded on May 19, 1536, just over three years after marrying the King.

This portrait is one of the only potential depictions of the queen that was produced in her lifetime. The inscription was added after her death by King Edward VI's tutor, who likely knew the queen well enough to identify her. However, this sketch shows her as blonde, when most sources agree that she was a brunette, but the yellow chalk might have been a later addition..

Jane Seymour, Hans Holbein the Younger (1536–37) Gemäldegalerie, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Jane Seymour was Henry's third wife and mother of King Edward VI. These two portraits of her were created while she was the queen, and show her wearing the fine jewelry provided by her new husband, as well as the English gabled hood, which was seen as an intentional contrast to Anne Boleyn's favored French hood.

Her time as queen was cut short, however, due to complications during childbirth that led to her death. Henry was reportedly deeply saddened by her death, but would go on to remarry three more times.

His next marriage to Anne of Cleves only lasted six months. Their union was a political move, and the marriage was declared unconsummated and annulled.

Henry's fifth wife was Catherine Howard, who married the then-49 year old king when she was somewhere between 15 and 21 years old. Like Anne Boleyn, she was accused of adultery and beheaded.

Henry's final wife, Katherine Parr, outlived him. She also had multiple marriages- King Henry was her third husband. After his death, she remarried her fourth and final husband, Thomas Seymour, the brother of Jane Seymour.

Jane Seymour, Hans Holbein the Younger (1536–37) The Royal Collection / HM Queen Elizabeth II

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset, Lucas Horenbout (ca. 1533–34). The Royal Collection / HM Queen Elizabeth II

Henry Fitzroy was King Henry VIII's first son, born out of wedlock to his mistress, Elizabeth Blount. Before the birth of Edward VI, King Henry VIII might have been considering naming Henry Fitzroy as his heir. The King gave his son several titles in order to increase his status, including Duke of Richmond and Somerset, Lord Admiral of England, and a Knight of the Garter.

Henry Fitzroy was well educated, and spent some time in the French court before marrying Mary Howard, sister of his closest friend, Henry Howard. He died young, succumbing to tuberculosis at only 17 years old.

This miniature portrait of the young duke was painted around the time of his marriage to Mary Howard. His exposed chest, nightcap, and undershirt tell us that this was likely an intimate portrait, based on the minatures that had become popular in France around this time.

Edward VI - The Boy King

Edward VI as a Child, Hans Holbein the Younger (1538). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

After Henry VIII's death in 1547, the throne passed to nine year old King Edward VI. Because Edward was so young, a Lord Protector of the Realm was appointed to govern until Edward came of age.

This portrait was painted in 1538 as a New Year's gift from Hans Holbein the Younger to King Henry VIII. The expensive clothes, with real gold and silver incorporated into the paint, along with the rattle shaped like a scepter make young Edward look like a king.

Some of the magnificence of the painting has been lost over time. Instead of the gray we see today, the background was originally a rich blue that would have contrasted with the bright red and gold of Edward's attire.

The inscription, written in Latin, encourages Edward to “emulate thy father and be the heir of his virtue."

Edward VI, Attributed to Guillim Scrots (ca. 1547–50). Compton Verney Art Gallery and Park, Warwickshire

In this later portrait of Edward VI, Guillim Scrots relies on both Tudor symbols and symbols from the ancient world to show the power of the King.

Most obvious are the red and white flowers, which allude to the red and white roses of the Lancasters and the Yorks, the two houses united under the Tudor name. All of the flowers in the painting turn towards Edward, telling us that he is more powerful than the sun.

The fact that Edward is shown in profile is likely a reference to ancient roman coins, where the emperor was always shown in profile.

Edward's reign was short, lasting only about six years until he succumbed to a lung infection at 15 years old. However, his devout Protestant beliefs did have a profound effect on England. He named Lady Jane Grey as his successor to try to keep the throne under Protestant control, though ultimately his Catholic half sister Mary would become queen. Portraits of Edward continued to be produced even after his death in support of the Protestant cause under Mary's rule.

Mary I - Bloody Mary's Catholic Resurgence

Mary I, Antonis Mor (1554).

Isabella Stewart Gardener Museum, Boston

After Edward VI's death, Mary declared herself queen and became the first woman to rule England uncontested. She was the daughter of Katherine of Aragon, Henry VIII's first wife.

In addition to ruling England, she was married to King Phillip II of Spain. In this portrait, the diamond pendant around Mary's neck was a gift from Phillip, and one of her rings was given to her by Emperor Charles V, her father-in-law. Mary was reportedly very fond of her jewelry, and showcased her collection in many of her portraits.

Both Mary and Phillip were devout Catholics and firmly opposed the Protestant Reformation that was sweeping through England. The people of England, however, were largely unwilling to return to Catholicism. Lands previously occupied by monasteries were now privately owned, and Protestant practices had become the norm under Henry VIII's and Edward VI's reigns.

This led Mary to begin ordering public executions of Protestants, earning her the title 'Bloody Mary'. She was not the only ruler to order heretics to be publicly burned- Henry VII ordered ten burning, Henry VIII ordered 81, Edward VI ordered two, and future Queen Elizabeth I would order four. Mary, however, demanded 283 public burnings during her five year reign, averaging at more than one every week.

Elizabeth I - Portraits of the Protestant Queen

Elizabeth I, Attributed to the workshop of Nicholas Hilliard (ca. 1599). National Trust, Hardwick Hall, The Devonshire Collection

The reign of Queen Elizabeth I was largely regarded as a time of stability and peace, despite the religious and political conflicts that had marked the reigns of her predecessors. She was politically savvy and a strong ruler, even earning the respect of the Pope, despite the fact that she was Protestant. Ambassadors from around the world came to meet with her, including the Sultan of Morocco, whose portrait hangs in the exhibition and who's visit likely inspired Shakespere's Othello.

She was popular amongst the people as well. Protestants that had fled during Mary's reign returned to England and commissioned gifts in her honor for her tolerance and kindness.

This particular portrait was commissioned by Bess of Hardwick, the richest woman in England besides Queen Elizabeth herself. Bess was known for her extensive collection of textiles, so it's no surprise that carpet and velvet feature heavily in the background of the painting. Even the queen's skirt, with embroidery of various plants an animals, might be a record of actual embroidery that Bess created for the monarch.

Elizabeth I (The Rainbow Portrait), Attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (ca. 1602). Marquess of Salisbury, Hatfield House, Hertfordshire

Queen Elizabeth I was reportedly very controlling of her public image. She wanted an official prototype of her appearance to be created to guide all portraits of her, and also ordered unflattering depictions of herself to be destroyed.

Despite the fact that it comes from the later years of the Queen's life, The Rainbow Portrait portrays her as a beautiful young woman. Many elements of the portrait are symbolic- like the band of light in her hand alluding to her ability to bring light to her subjects, but much of her attire is real, having been linked to real inventories of her possessions.

Crispijn de Passe's Elizabeth I gives us a more realistic view of the queen. Here, we can see her wrinkles and possibly a more accurate depiction of her features. In this work, she looks much older, despite the fact that it predates The Rainbow Portrait by ten years.

Elizabeth I,

Crispijn de Passe the Elder (1592). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester & Elizabeth I,

Federico Zuccaro (1575). The British Museum, London

Elizabeth I was known as the 'Virgin Queen' because of her refusal to marry and the fact that she bore no children, but she did allow herself to be courted by a handful of suitors throughout the years. Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, was one of her favorites.

Even when shown in association with one of her suitors, Elizabeth's morality was still a focal point of the work. A dog and an ermine sit on the column behind her, representing fidelity and purity.

Because she remained unmarried and childless, Elizabeth's reign marked the end of the Tudor dynasty. After her death in 1603, the throne passed to King James I, the great-great-grandson of Henry VII, great-grandson of Henry VIII's sister, Margaret.

Special thank you to the Cleveland Museum of Art for providing the images and information for this article. If you want to learn more about the Tudors and the art from the English Renaissance, I highly recommend the official catalog The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England by Elizabeth Cleland and Adam Eaker. The Tudors will be on display at the CMA through 5/14/2023.